Quotation

“…every victorious second nature will become a first.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche

Visual statements often make use of quotation-direct allusion or reference to well-known passages of works from the past-to establish the authority of a new voice or a fresh perspective. Artists have, paradoxically, often used the pictures of others to differentiate their own particular position. The act of quotation takes many forms, from the ostensibly direct mode of copying, or the insertion of elements borrowed from elsewhere into a new picture, to the translation of a recognizable composition or subject matter into a new idiom or personal style. This exhibition gathers together works, many from the collection of the Confederation Centre Art Gallery, that quote famous works of art to different ends.

Perhaps the most obvious form of quotation is the copy. Artists have often learned their trade through copying great works from the past. Both technique and understanding can be learned in this way, but the choice of what is copied can also be a form of identification; the artist demonstrates allegiance to, or recognition of, a particular master, as well as his or her ability to face the challenge posed by other works. Like many Canadian artists of the late 19th century, Robert Harris built his craft and reputation through close examination and imitation of the art of European Old Masters like Diego Velázquez. Not only did he make copies of Las Hilanderas and Las Meninas, which he saw at the Prado in Madrid, but his choice of where to crop the images tells us much about what he found important. In his copy of Las Hilanderas, for example, he focuses on the spinning woman in the right foreground of the picture, often seen by commentators a representation of the painter as humble, labouring craftsperson, close to the earth and the materials of his or her trade. Even as he takes on one of the greatest of European painters, Harris positions himself more as a matter-of-fact worker than an airy maker of visual ideas.

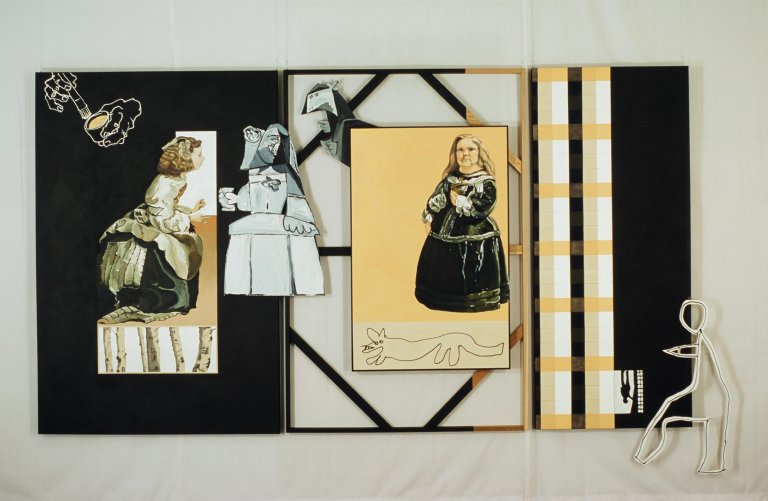

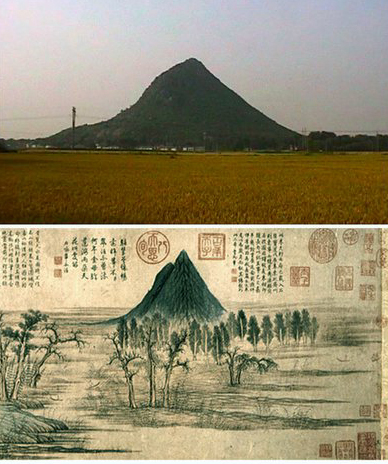

Velázquez’s most famous work, Las Meninas, is on the other hand often thought of as a pioneering conceptual picture, establishing the intellectual authority of the artist through the placement of his own portrait within the picture as a privileged viewer. Since quotation can reveal as much about the primacy of a given view or interpretation of a work as it does about the quoted piece itself, Las Meninas has often been reconsidered by artists examining the conditions of viewership. Adad Hannah has made numerous videos and photographs in which the viewing of art is the primary subject matter, and it is no accident that he has made pictures of people viewing Las Meninas itself. In these videos, we see how the old masterpiece continues to function in the present. Hannah reactivates the picture through the placement of viewers holding a mirror, extending the picture’s famous reflective surfaces into a contemporary space. The frozen poses of the viewers remind us how masterpieces hold our attention and respect, but the work equally demonstrates the impossibility of a static view of the past, as minute movements of the subjects are registered over time. The act of quotation can also illuminate the passage of time more explicitly. Hank Bull’s split-screen video of two mountains that appear in one of China’s most famous landscape paintings captures the present conditions in China vividly, showing changing relationships to two stable forms that have often served as symbols of the eternity of the nation. In the same image we register the presence of primeval geological figures and ancient patterns of land use alongside new ways of using or moving across space, and new mediums for capturing it visually.

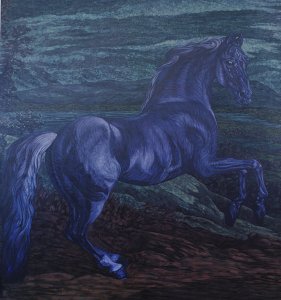

Changing vision is perhaps the central subject matter of Leslie Poole’s multigenerational, layered take on, again, Las Meninas. Responding both to Picasso’s lifelong engagement with the picture and the original painting that still hangs at the Prado, Poole further complicates the image by breaking it down into its parts and inserting himself directly into the picture through various autobiographical references-to his own painterly hand, to autobiographical incidents and contexts, to his own face. Lucy Hogg’s assertion of changing vision is an activist one, a direct challenge to the authority of masterpieces. Using lurid, theatrical colours to repaint “museum pieces” as apocalyptic, inverted echoes, then strategically placing them in prominent collections, she intervenes in art history through perverse repetition. Where Hogg’s work depicts great works in a state of apparent ruin, Salmon Harris revives a lost masterpiece through repetition. Here he remakes in a contemporary style Robert Harris’s 1884 mural for the Parliament Buildings, The Fathers of Confederation, lost in a fire in 1916. His works are based both on photographs of the painting and the extant sketches that preceded it, confounding the temporal location of a work that is no longer available to us, and further registering both our permanent distance from, and the endless reusability of every original.

Pan Wendt, curator