Holding the Pose: Portraits from the Collection

This exhibition presents a selection of portraits from the collection of the Confederation Centre Art Gallery. Combining historical portraiture with contemporary representations of individuals and groups, it provides an overview of the genre in Canada, its many approaches and its transformation over time, with a particular focus on the way the subjects of portraiture have played a part in the resulting work-their attitude, their mode of address, their self-presentation, and the way their pose is as much the subject of the work as their physical likeness. Portraits are ultimately the result of an encounter between artist and sitter. The exhibition’s starting point is the work of Prince Edward Island artist Robert Harris (1849-1919), who was in the late 19th century one of Canada’s most prominent portrait painters. Harris’s portraits functioned in dialogue with the rapidly spreading phenomenon of commercial photography. His work showcased the artist’s brushwork and skill at capturing a natural-seeming likeness, adhering closely to longstanding traditions of the formal, celebratory depiction in opposition to the emerging, and increasingly easy availability of the photographic image. His pictures define subjects as enduring monuments. Composed, regal sitters emerge from dark backgrounds as volumetric, physically imposing images of importance, accentuated by gilded frames. The aesthetic of portraiture is one of elevation and solidity, likeness as preservation and celebration.

The marriage of naturalness and monumentality in Harris’s work was a response not only to the photograph’s documentary power, but also to the more openly artificial images of aristocratic self-presentation exemplified in this exhibition by the work of Thomas Mower Martin. In the century following the heyday of Robert Harris’s official portraiture, modern contingency-the uncertainty of the individual’s position in the world-invaded and transformed the portrait genre. In an era when anyone could and should be a worthy subject of an image, the recording of individual lives adapted by concentrating on the ways that individuals both defined and exceeded the conditions of their existence.

The identity of the sitter is central to the portrait’s function, as it strives to establish the uniqueness of the person and his or her place in society and history. In the past century, the celebratory presentation of individual identity has been targeted by a wide-ranging critique that has redefined the genre. From George Pepper and Kathleen Daly’s quasi-ethnographic paintings of people who are meant to define a multi-ethnic nation, to Barbara Astman and KC Adams’ pictures of subjects positioning themselves in relation to popular gender and racial stereotypes, it is clear that portraiture now functions as part of a play of representations of identity. In this context, the naturalness of the late 19th century pose can no longer be taken for granted. Even the celebration of historical figures can be represented as a highly mediated form of theatre, as in the prints of Rémi Belliveau, with their ironic golden frames.

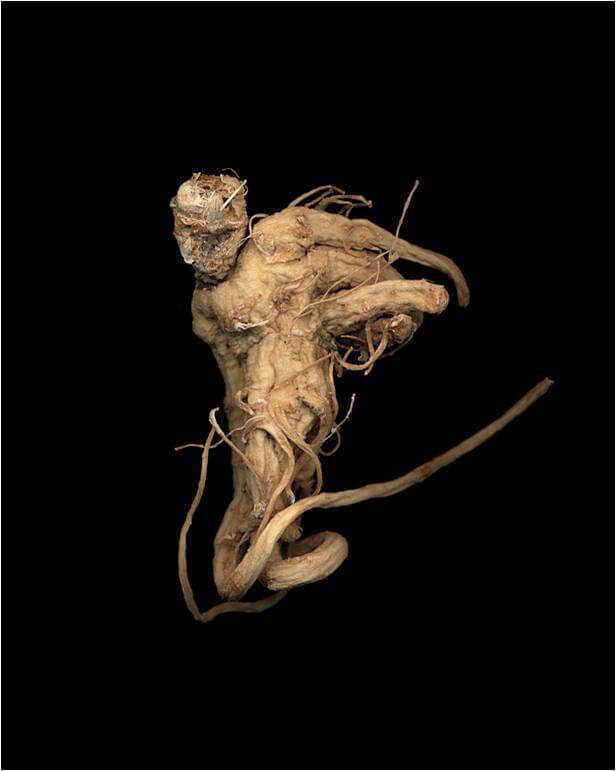

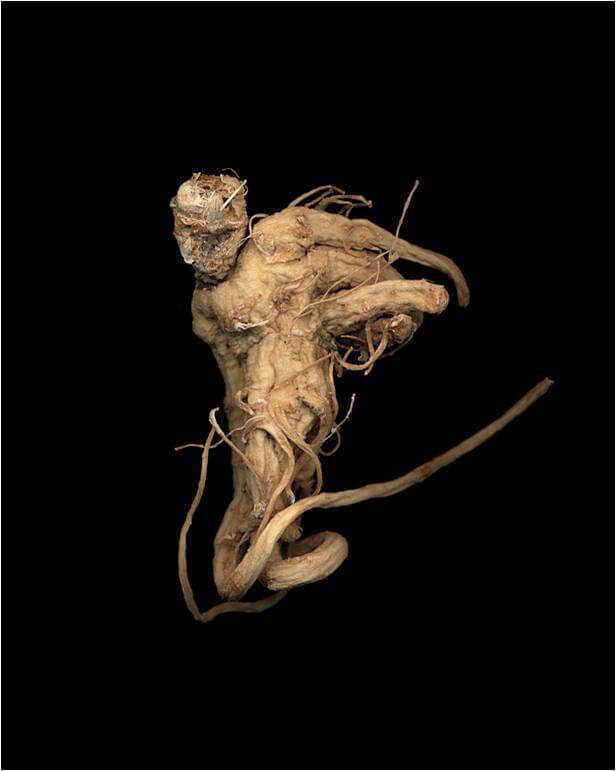

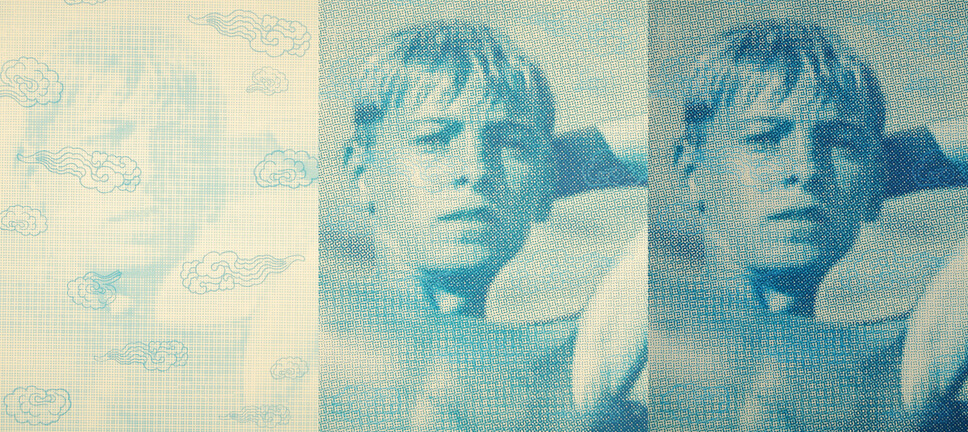

The pose itself and its status as a record can be represented tragically, as a kind of habit or trap of seeing. Edward Poitras physically equates the hanging of Louis Riel with the production of his image as a national hero. Dan O’Neill and Stephen May present the seductive pose as a received image, the individual subject filtered through a layer of associations that complicate the sitter’s agency. In the work of Prince Edward Island painter Brian Burke, presented here as a counterpoint to the legacy of Robert Harris, the pose becomes vulnerable, the subject’s self-presentation and visual isolation deeply ambivalent, even oppressed by a flattened space that nonetheless leaves the position of the sitter open ended. Burke’s portraits represent the potential and limitations of contemporary freedom and uncertainty.

-Pan Wendt, Curator