David Alexander: The Shape of Place

The landscape is the evidence.

– David Alexander

David Alexander was born in 1947 in Vancouver, BC. He was familiar with art from an early age, especially that of BC-based artists, such as Emily Carr. He grew up along the west coast, going to high school in Steveston, BC, and then attending art school in Nelson, BC at the Kootenay School of the Arts (then affiliated with the now defunct Notre Dame University). In 1979, Alexander attended a summer workshop for professional artists at Emma Lake, Saskatchewan, and because of his positive experience there, moved to Saskatoon the following year to attend graduate school at the University of Saskatchewan. He stayed on in Saskatoon until moving to Kelowna, BC to live and work in 2003. The artist has travelled widely, both to look at art in museums, and to explore various remote or unusual landscapes in far-flung places.

Alexander’s paintings are characterized by their intensity of vision, strong, vibrant colour, and convincing sense of the particularities of place. He works to personally extend the meaning and role of landscape painting as a contemporary activity and field of thought and endeavour. In his hands, landscape painting survives as a valid, living pursuit, not something relegated to the past. It could be said that his work is actually not so much about landscape as it is about nature, and one’s experience when immersed in the natural environment.

Alexander has exhibited widely and is represented in many corporate and public collections in Canada. A multiple-authored book on his work published for the Kelowna Art Gallery by McGill-Queen’s University Press accompanies this exhibition.

♦

The Artist’s Early Work

Landscape is our big vessel into which we put both good and bad things.

When David Alexander moved to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 1980, he set himself the challenge of learning to paint the prairie—a daunting task. He feels it took him almost a decade to understand the prairie landscape, with its flat, windswept, almost featureless expanses, and huge skies with towering cloud formations.

During the 1980s, Alexander was able to travel outside of Canada several times, researching work by other artists in museums and galleries, meeting artists, curators, and critics in London (UK) and New York, and going on sketching trips in remote places. His first trip to the Arctic was to Ellesmere Island in 1988, a grueling two-week hike of sixteen-hour days.

The artist received his MFA from the University of Saskatchewan in 1985, and completed the thesis component of his degree on the work of the French Impressionist artist Claude Monet. He was particularly interested in how Monet’s deteriorating vision in his senior years affected his pictorial structure. Alexander made a few research visits to Monet’s house and garden in Giverny, not far from Paris. Alexander also made a sketching/walking trip to Orkney Island in Scotland in 1989.

In his work from the 1980s, Alexander moved from flat surfaces and thinly applied paint to more muscular forms that have more implied three-dimensionality and a thicker, more emphatic paint application.

♦

David Alexander’s Work from the 1990s

Rhythm in my work comes from physically being in the landscape, not sitting back as a voyeur, but actually walking through it, up it, over it, and back over it again. That’s when I begin to understand that movement of land.

During Alexander’s second decade in Saskatoon, he was able to travel more extensively, producing drawings or small paintings on site in various places that could feed into large paintings once he was at home in the studio. He had long been drawn to northern places, as well as Canada’s alpine regions/environment. He usually hiked in the Rockies once or twice a year, and also had two trips to Iceland (in 1999 and 2002), as well as a journey to Greenland and Baffin Island in 1993. He and his wife made a trip to Newfoundland in 1998, and then visited there every summer until they relocated to the Okanagan Valley to live in 2003.

In several paintings from this period, the artist used his invented conceit of depicting a giant flower blooming in front of the barren Arctic landscape. This bizarre juxtaposition further heightens the innate aspects of each of the elements: the inhospitable but impressive Arctic landscape, and the fleeting colour and improbable beauty of a tropical flower.

♦

David Alexander: Further Afield

The [mountain] paintings that make the most sense for me are those where I learn about the particular shape of a range.

In the first decade of this century, David Alexander continued his practice of making it a priority to travel to remote destinations with the aim of producing paintings based on where he had walked and what he had seen and experienced. He moved from Saskatoon to Kelowna, BC, in 2003, but has not pursued painting the Okanagan landscape. Instead, he has made sketching/research trips to California, Japan, Argentina, the Arctic (by boat), and the Grand Canyon. However, he continues to hike in the Rockies and in the other mountain ranges in BC. Thus, there are several paintings of alpine subjects in this section of the exhibition. In these, we sense the artist’s aim to understand the structure and shapes of the forms that make up the mountains in which he is situated. Alexander readily changes the format of his canvases depending on the subject he is exploring. Rectangles of either vertical or horizontal orientation are interspersed with near-square paintings, and his highly effective long panoramic-format paintings

♦

David Alexander’s Wet Series Paintings

With the paintings in the Wet series, I realized that water surfaces hold all the landscape around them, including the sky.

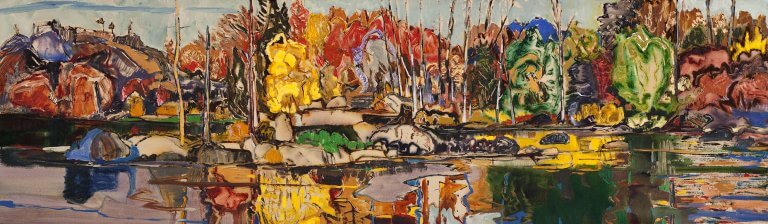

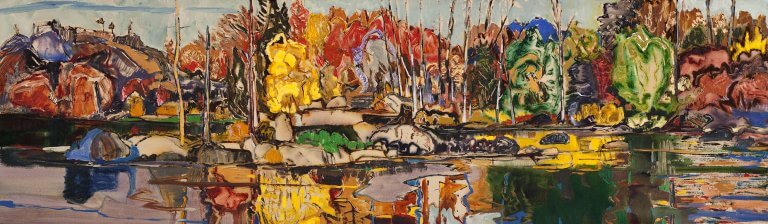

Beginning in 2004 (after an initial inspiration in 2001), Alexander began to focus a great deal on water surfaces as a jumping off point in his paintings. Whether these were observed and photographed as surfaces of ponds, lakes, alpine tarns, or river pools, the artist was interested in fleeting colour and light effects.

He was also intent on establishing an interplay between his depiction of the surface of the water and the flatness of the picture plane in his painting. This is not a one-on-one, direct relationship as he first establishes and then plays with it, but an elastic and slippery one. His so-called Camouflage series, within his overall Wet series of works, takes things to a visual extreme, polarizing the colours observed in the water’s ripples, and creating striking paintings that have engaging and unusual optical effects.

One could postulate that for Alexander the Wet series is something of a return to Monet, on whom he did his MFA thesis in the early 1980s. But no artist can paint a pond’s surface and not have to encounter Monet’s virtual “ownership” of the subject. In Alexander’s hands it becomes truly his own, and his work with shape, colour, space, and emotional and mood effects are truly remarkable.