From Housebuilder to Architect: Charles B. Chappell‘s Charlottetown

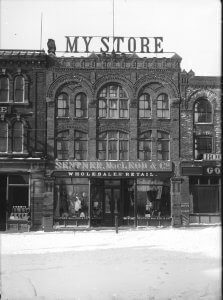

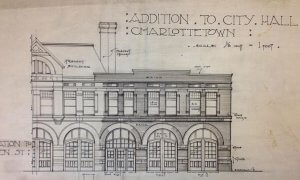

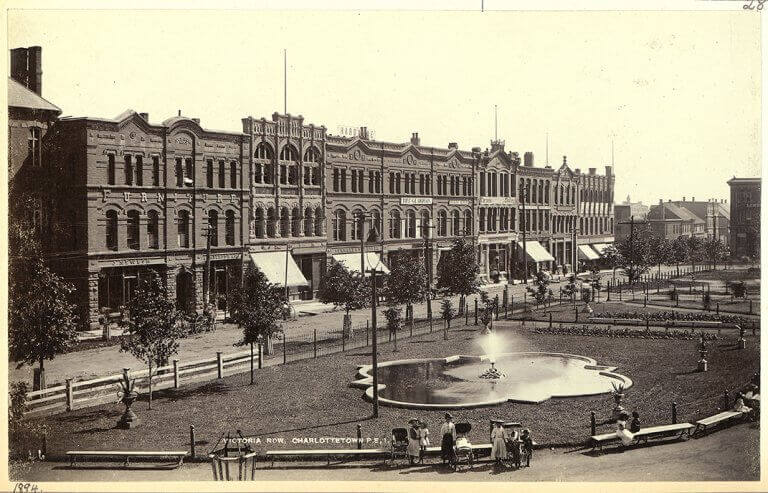

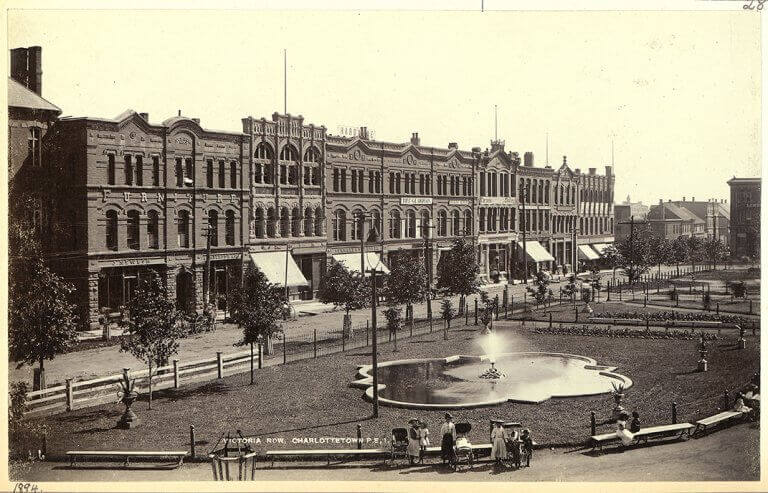

In the late 19th century, the profession of architect was emerging on Prince Edward Island. Most private buildings and many public structures were designed by men whose training was in practical experience as housebuilders. One of these, Charles Benjamin Chappell, has left his mark on Charlottetown with credit for designs to more than 100 buildings in the city. Chappell trained with Lemuel Phillips, becoming his partner, and at the age of 30 was credited with more than 30 buildings, several of which helped define the Victorian streetscape facing Queen’s Square. In 1884, the success of the partnership led to Romanesque Charlottetown City Hall, perhaps his most noteworthy structure.

Unlike his contemporary and competitor, William Critchlow Harris, Chappell did not develop a distinctive architectural style. His designs span a range from vernacular through Romanesque, Queen Anne and bungalow, deftly responding to the changes in architectural fashion and the whims of his clients. His output is noteworthy not only for design, but also for the range of structures to his credit. His drawing board was open to clients with requests for modest double tenements, but also for ornate houses for the city’s elite. While there are scores of residences for which Chappell supplied designs, he also took commissions for schools, hospitals, market buildings, churches, stores, railway stations, warehouses, factories and theatres. Chappell practised alone from 1895 until 1915 when he invited a Scots-born architect John Marshall Hunter to join the firm which continued until Chappell’s death in 1931.

While the bulk of his work was in Charlottetown, his designs can be found across the Island and throughout the Maritimes, especially in the 1900s boom town of Sydney, Cape Breton.

Working in the city for a span of 50 years, Chappell and his partners have left a mark which is not always recognized. A dozen of the buildings facing Queen’s Square are the work of Chappell as are single and double residences throughout the city, especially in the neighbourhoods which developed in the period from 1890 to 1920 such as Brighton and Upper Prince Street. His public buildings have fared less well with structures such as Prince of Wales College, The Opera House, Heartz Hall at Trinity Church, and the Exhibition Building and Grandstand falling victim to fire. However, surviving structures such as Zion Presbyterian Church, St. Paul’s Anglican Church Hall, the old Prince Edward Island Hospital on Kensington Road, several stores on Victoria Row, and scores of residences, attest to the fact that Charles B. Chappell has been responsible for more buildings in Charlottetown than any other architect in the city’s history and has helped define the look of the capital.

Harry Holman, Curator